Time is. Time was. Time past.

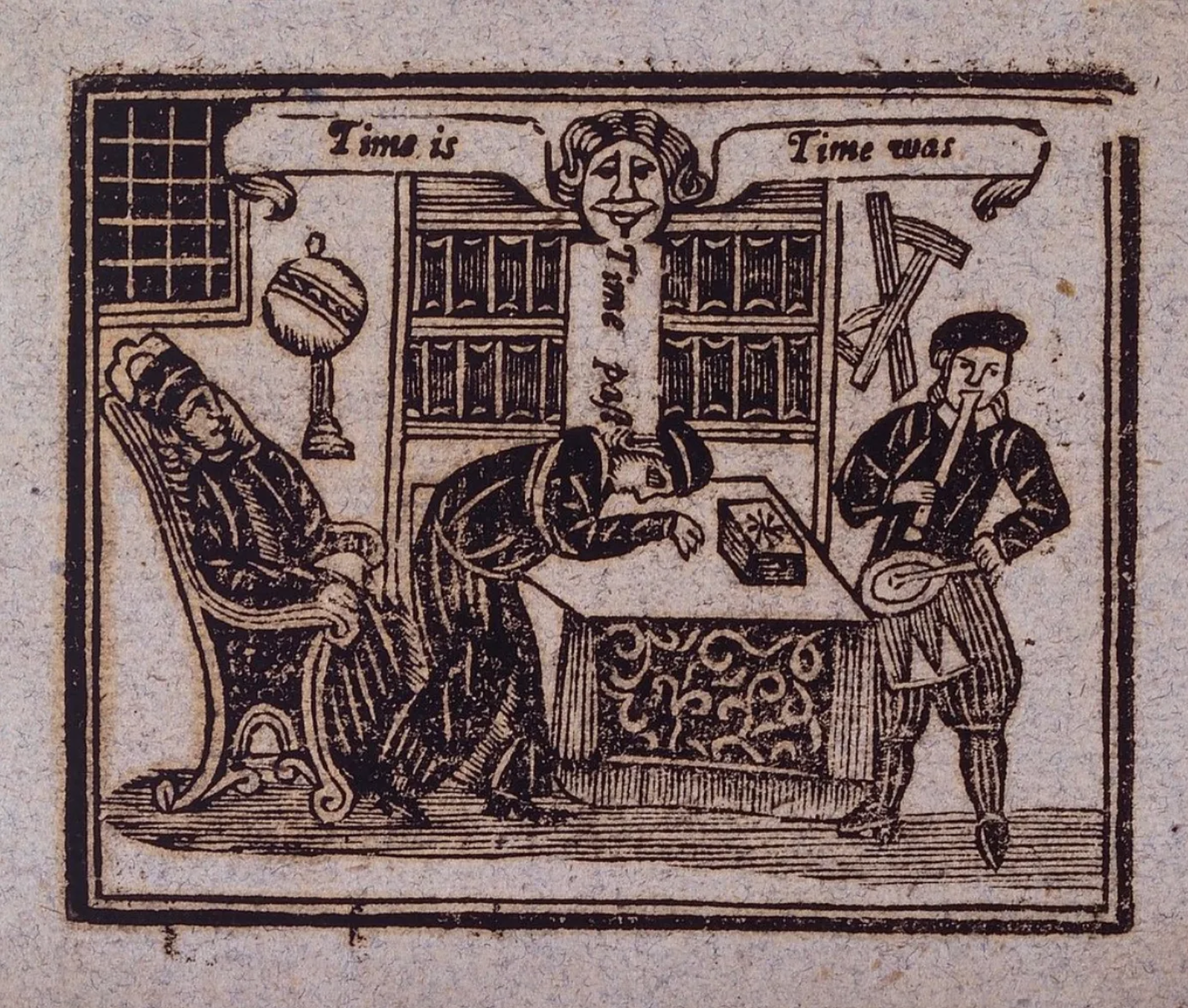

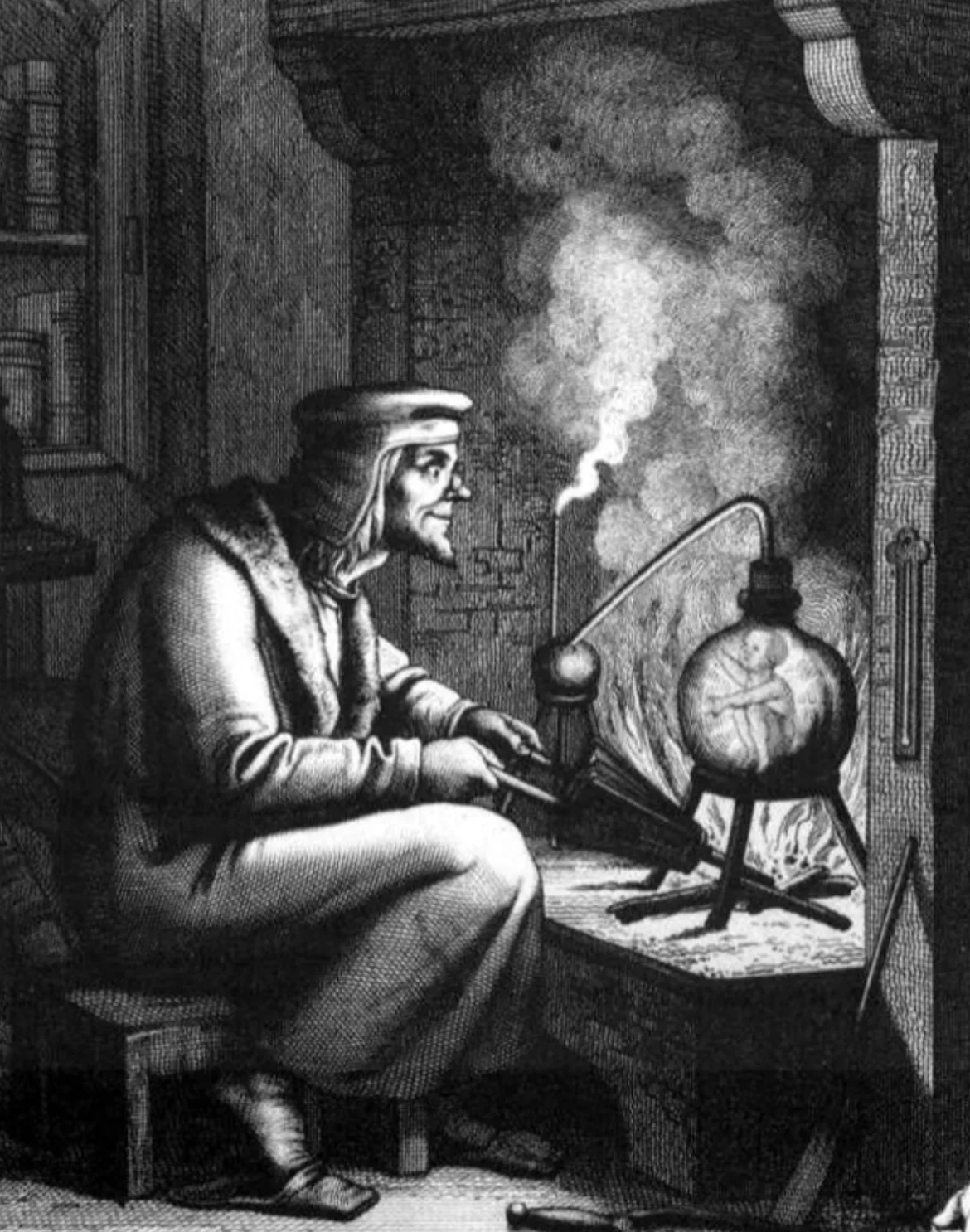

A man sleeps between Roger Bacon (?) and a musician: a brass head proclaims time present and the past. Woodcut, ca. 1700-1720. Via Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

Here, a tale of a peculiar brass head, alchemical inklings, and conjuration in the West.

“Time is. Time was. Time past.”

— The words spoken by a peculiar and sorcerous brass head just before it shatters upon the ground.

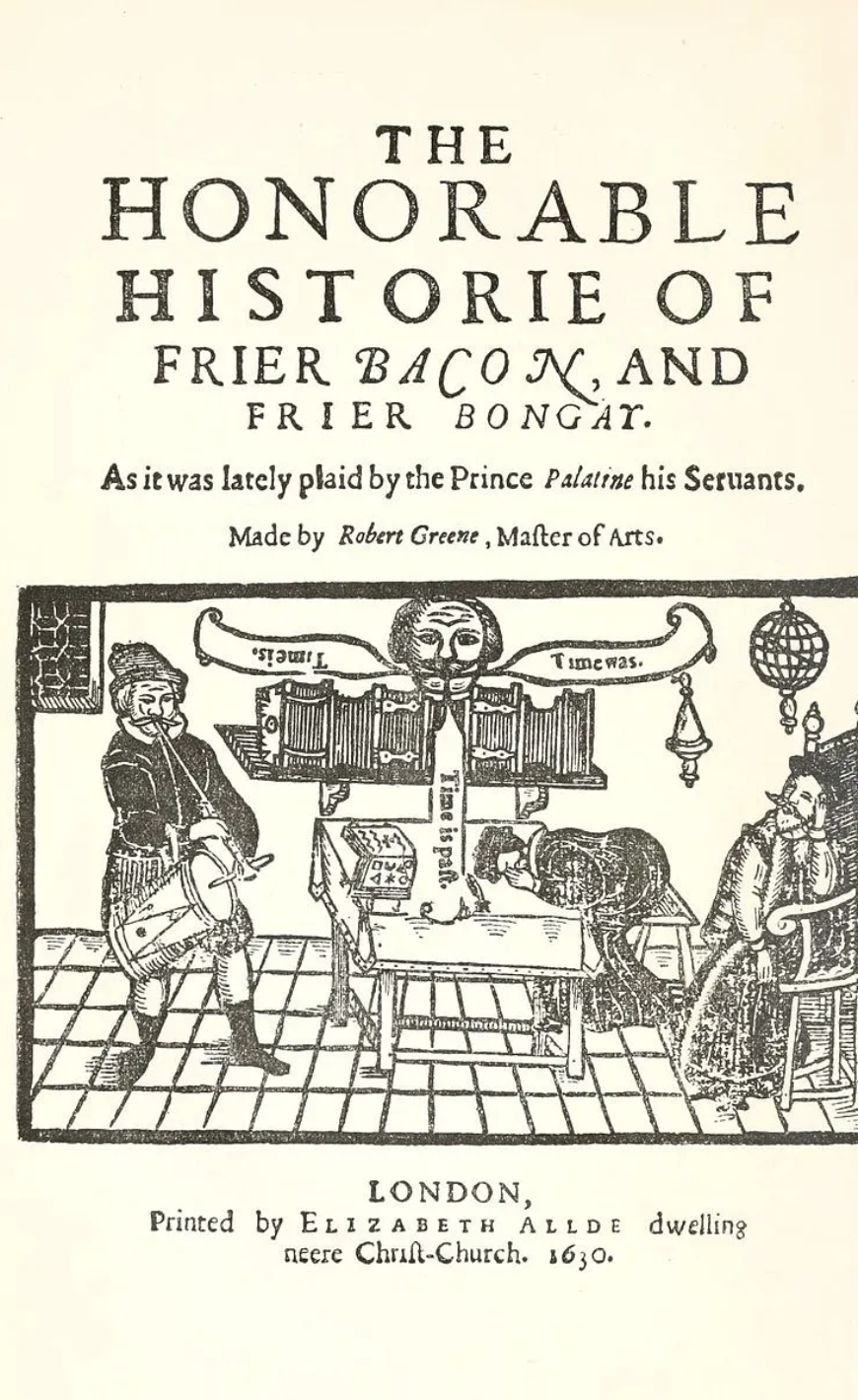

The event takes place Robert Greene’s play The Honorable Historie of Frier Bacon and Frier Bongay. The play — a comedic piece from the Elizabethan period — holds a complex interplay of plots, and concerns itself with a magical iteration of the 13th century English polymath Roger Bacon.

Title page of the 1630 printing of Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay. The engraving shows the magical talking brazen head at top. Title page of reprint of 1630 edition of Robert Greene's Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay. Via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

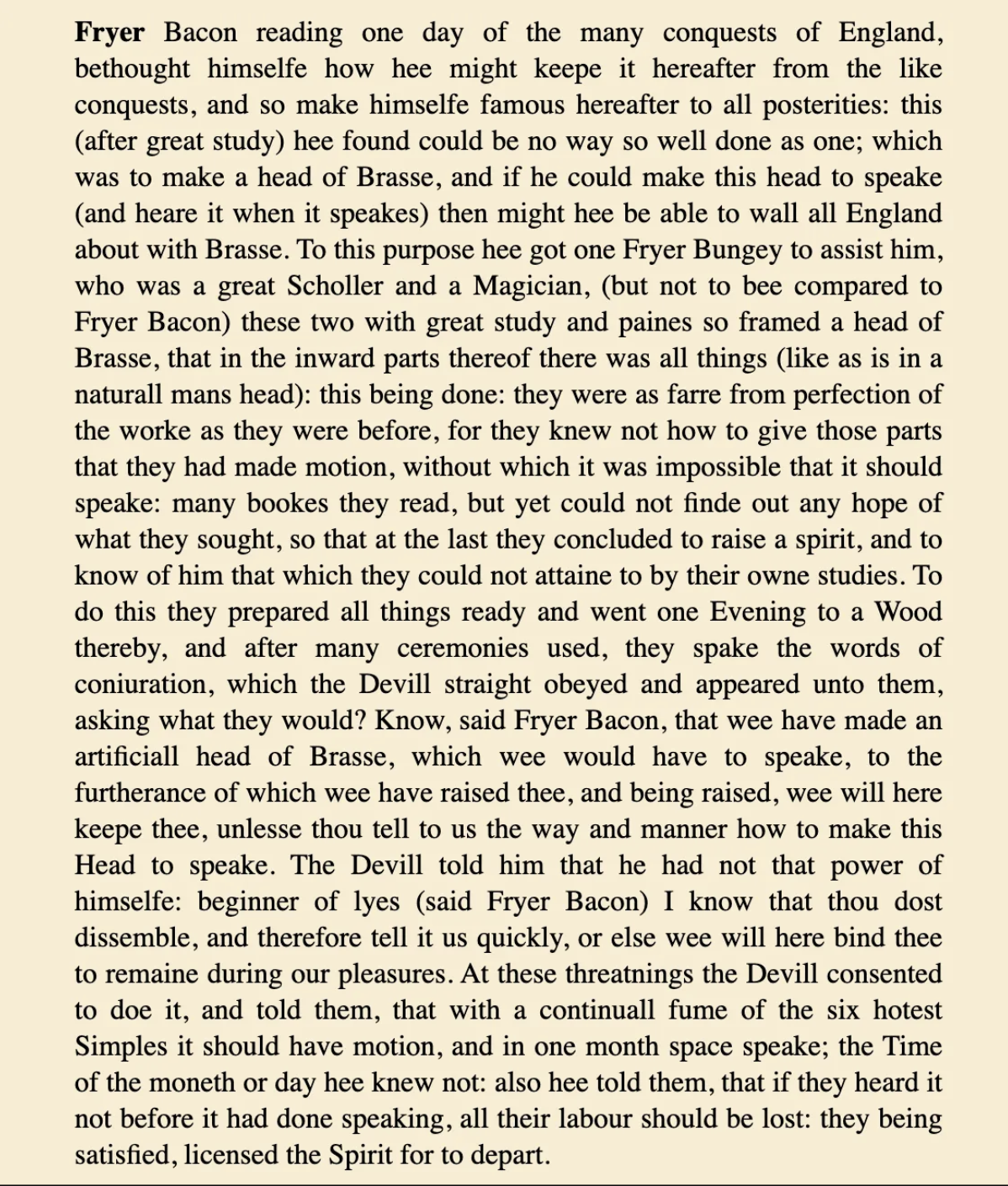

While the play contains a vast number of elements, the scene in which this line was spoken concerns Friar Bacon and a partner named Friar Bongay. In the scene, the two friars endeavor to create a talking head made of brass. This brass head would be sprung to life by magical means, particularly through assistance of demonic forces. It would then encircle all of England with a wall also consisting of brass.

However, due to the insidious arrival of sleep and human error, the operation goes awry. Just before falling and shattering, the brass head exclaims:

“Time is. Time was. Time past.”

The University of Chicago maintains a detailed page concerning Sir Thomas Browne — who we will read about shortly, and who penned his own explication of the play. The full text of the history and explication is included there. The main portion detailing the making of a brass head, or head of “Brasse,” can be seen below sourced from the University’s page:

Brass head passage in The Honorable Historie of Frier Bacon and Frier Bongay. Via University of Chicago.

At the end of the play, shaken to the core by a deadly magical duel, Friar Bacon turns his back on magic for good, seeking to redeem himself and repent for its acts. Friar Bacon’s servant Miles — whose folly resulted in the shattering head — finds a job in hell, bounding off into damnation with the devil.

One fascinating and evocative depiction of the scene may be viewed in a woodcut shown below. It is dated c.a. 1700-1720. The artwork is held by the Wellcome Collection in London.

A man sleeps between Roger Bacon (?) and a musician: a brass head proclaims time present and the past. Woodcut, ca. 1700-1720. Via Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

Some years later, the aforementioned Thomas Browne, himself an English polymath, admonished that:

“Every ear is filled with the story of Frier Bacon, that made a brazen head to speak these words, ‘Time is.’ Which though there want not the like relations, is surely too literally received, and was but a mystical fable concerning the Philosophers great work, wherein he eminently laboured…”

Bemoaning the literal interpretation of the work, we find a reference to the Great Work of the philosophers. Here, alchemical murmurs are detected.

It is no surprise then, that in Thomas Browne’s 1672 edition of Pseudodoxia Epidemica VII, the “Time is…” phrase is briefly mentioned. The explication found in Pseudodoxia contains a number of alchemical references that are particularly fruitful for engagement.

Browne writes:

“…implying no more by the copper head, then the vessel wherein it was wrought; and by the words it spake, then the opportunity to be watched, about the Tempus ortus, or birth of the mystical child, or Philosophical King of Lullius: the rising of the Terra foliata of Arnoldus, when the earth sufficiently impregnated with the water, ascendeth white and splendent. Which not observed, the work is irrecoverably lost; according to that of Petrus Bonus […]

The references here point to alchemical figures like Ramon Llull, Arnaldus de Villa Nova, and Petrus Bonus.

Alchemical figure Michael Maier is even faintly implied on some level in the phrase “Terra foliata” — The sixth emblem of Maier’s work Atalanta Fugiens — is that of a figure sowing gold in "“Terra Alba Foliata” (the White Foliated Earth) for the sake of a mystical reaping of that which is sown.

The passage also concerns the birth of the mystical child — a concept that maps onto the alchemical Filius philosophorum: The Philosopher’s Child. This is the birth of a “child” which is sprung from the Coniunctio, or conjunction, of oppositional forces. Often, these forces are represented by the alchemical White Queen (White Mercury) and Red King (Sulfur).

Yet, in a broader magical sense, the play concisely details what is perhaps the essential form of Western magic. It is one rooted in a kind of Faustian impulse. Indeed, the play has overlaps with the story of Faust’s own conjuration efforts.

The image above is cataloged as "19th century engraving of Homunculus from Goethe's Faust part II." It comes from Wikimedia Commons, where it is listed under CC criteria via Public Domain.

A figure who expresses this impulse particularly well is poet and mystic Dale Pendell.

Pendell spoke about the ‘mythopoetics of shamanism’ in the western tradition. One feature Pendell spoke about is that of Faust — or in our case, the Friars —as a prototypical, or archetypal, western shamans. Further, Pendell expressed necromantic conjuration as a kind of quintessential practice of Western magic.

Pendell expresses that the act of giving spirit a body is a very deep-rooted facet of the western magical traditions. Consider the homunculus, one like the head found in Greene’s play. If one begins practicing the act of thinking conjurationally about our world, so to speak, one may find that this is evident all the way to Western modernity.

For example, Pendella sks us to consider the corporation, which originally exists as a kind of spirited or abstracted entity. It is embodied and enfleshed through the magic circle of the court. Further, it is bound by the incantations we call the law: in turn, the Corporation-as-Person emerges.

In other words, Pendell says, consider a spell to be that which binds perception in order to form a consensus reality. This process is often wrought with danger, demonic forces, and misfortune.

This necromantic act of giving spirit a body can thus be incredibly dark and destructive, as is the case with both the corporate entity and the brass head. So much so that it literally consumes other beings, and even World itself.

Pendell, in a comparative lens, relates this consumption to Preta (प्रेत / ཡི་དྭགས་ / yi dags) — the realm of hungry ghosts in Buddhism, who are the manifestations desire and hunger itself in the deepest sense. Pendell expresses that, for many first peoples of Americas, shamanism is a kind of “ghost work.” In this way, a number of traditions may be similarly linked.

Pendell says: "All shamanism is ghost work, but Faustian magic is conjuring: giving a body to a ghost. Or, we could say, to an abstraction.”

In turn, the brazen head in Greene’s play can be seen as a persistent motif with roots in the very essence of Western magic, and even scientific pursuit. It is no surprise that the play appears on the fringes of modernity: magic & science had not yet been fully extricated, and the mystical impulse — woven like a thread containing myriad themes — deeply colors the work.

When the alchemical quality of the play, as referenced by Browne, is factored in, we find the work to be a microcosm of the European magical mind of the period.

Bibliography:

Browne, Thomas. The Famous Historie of Fryar Bacon. Via University of Chicago.

Browne, Thomas. Pseudodoxia Epidemica Or, Vulgar Errors. VII. 1672. Via University of Chicago.

Greene, Thomas. The Honorable Historie of Frier Bacon and Frier Bongay. 1590. Link to play.

Pendell, Dale. Four Political Poems. Dale Pendell webpage.

Pendell, Dale. The Mythopoetic Roots of Psychedelic Practice in the Western Tradition. From the World Psychedelic Forum in Basel. 22. March 2008